译者按 - 牛津高阶英汉双解词典第七版第 1589 页对 propaganda 的解释:

noun (U) (usually disapproving) ideas or statements that may be false or exaggerated and that are used in order to gain support for a political leader, party, etc. 宣传;鼓吹:enemy propaganda 敌方的宣传 a propaganda campaign 系列宣传活动

There once was an old German education professor who also happened to be a magician. He would sometimes entertain drifting students with an unexpected magic trick during class, like pulling a coin from a sleepy student’s ear. If a student happened to compliment him on his ability, he’d mumble, “Keine Hexerei, nur Behändigskraft.” Which means: “No magic, just craftsmanship.” The craft he spoke of entails engaging the viewer in a visceral way to create a new reality (a “perceived” reality that is, by no coincidence, in harmony with the intent of the director,) and this “created/fantasy” reality then promotes a stronger emotional bond to the subject by diluting any detachment the viewer may have had previously. Much like the master illusionist, the propagandist works in the same way, swaying and influencing public opinion by means of creating a disassociation between public opinion and personal opinion. In so doing he utilizes the natural confusion that results from humanity’s need to translate their beliefs into reality and creates or manipulates a supposed desire for action. Simply put, propaganda tells you an idea is true, and then reinforces its assertion by fooling you into believing you came to the conclusion independently - or even better, that you had held the belief all along.

从前有一位年迈的德国教育学教授,他正好也是一位魔术师。他有时会在课堂上表演出人意料的魔术,吸引那些走神学生的注意,比如从睡眼惺忪的学生耳朵里拿出一枚硬币。如果一个学生碰巧称赞他的能力,他会咕哝着说:「Keine Hexerei, nur Behändigskraft.」意思是:「没有魔法,只是技艺」。他所说的技艺,需要让观众以一种发自内心的方式去创造一个新的现实(一种「感知的」现实,绝非巧合,这与官方的意图相一致) ,而这种「创造的/幻想的」现实,通过稀释观众之前可能有的割裂感,促进了与魔术主题更强烈的情感纽带。和魔术师一样,宣传者也正是这样工作的,他们通过创造公众意见和个人意见之间的分离,来影响和左右公众意见。在这一过程中,他们利用了人类的自然的混淆特征:人们需要将他们的信仰转换为现实,并创造或操纵一种假定的行动欲望。简单地说,宣传告诉你一个观点是正确的,然后通过欺骗让你相信你是独立得出该结论的,或者更极端的情况下,甚至让你相信自己一直持有该信念。

Interestingly, not long before the popularization of propaganda, Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud pioneered the study of human will in correlation with the conscious and unconscious being. He proposed that man did not in fact enjoy the luxury of free will, but rather was a slave to his own unconscious; that is to say all of man’s decisions are governed by hidden mental processes of which we are unaware and over which we have no control. Most of us largely overestimate the amount of psychological freedom we think we have, and it is that factor that makes us vulnerable to propaganda. Drawing directly from the studies of Freud, the psychologist Biddle demonstrated that “an individual subjected to propaganda behaves as though his reactions depended on his own decisions… even when yielding to suggestion, he decides ‘for himself’ and thinks himself free — in fact he is more subjected to propaganda the freer he thinks he is.”

有趣的是,在宣传普及之前不久,奥地利心理学家西格蒙德·弗洛伊德开创了人类意志与有意识和无意识的相关性研究。他提出,人类事实上并没有享受到自由意志的奢侈,而是成为了无自我意识的奴隶; 也就是说,人类所有的决定都受到隐藏的心理过程的支配,而我们并不知道这些过程,也无法控制这些过程。我们中的大多数人都高估了自己心理上的自由度,而正是这种因素使我们容易受到宣传的影响。心理学家比德尔直接从弗洛伊德的研究中得出结论:「受到宣传影响的个体,表现得好像他的行为取决于自己的决定…… 即使不得不听从建议,他也会决定『为自己』,并认为自己是自由的 —— 事实上,他认为自己越自由,就越容易受到宣传的影响。」

The successful use of propaganda depends on the creator generating some emotional response in the viewer. If the subject is political, for example, then fear (the most popular), moral outrage, patriotism, ethno-centrism, and/or sympathy are typical responses that the propagandist might try to elicit. This is done by attacking the surface consciousness of the masses and creating a disassociation between public opinion and the propagandee’s personal opinion. In doing so, the individual will work out “justifications and decisions for behavior which will conform to social demands in such a way as to make him least aware” of his guilty conscience.

宣传的成功运用取决于创作者在观看者中产生的一些情感反应。例如,如果主题是政治性的,那么恐惧(最受欢迎)、道德愤怒、爱国主义、种族中心主义以及同情,就是宣传者可能试图引起的典型反应。这是通过击破群众的表面意识,制造公共观点和普通人的意见之间的分裂来实现的。通过这样做,个人会为那些符合社会需求的行为找出「理由和决定,使他尽可能不意识到」自己的罪恶感。

The notion of propaganda is one whose origin could probably be traced back to the dawn of man. If the people of a tribe were in need of food they would come together around the fire, call to the hunter, inform him as to the necessity of food from the next hunt, and the hunter would be forced (by both responsibility and his conscience) to go out the next day and do his best to bring back food for the tribe. Here we can imagine the first sign of man acting regardless of his own desires in the name of societal betterment. Surely he is not the only one capable of finding and delivering food, yet he has accepted this role and does it to the best of his abilities when called upon to do so simply because it is so.

宣传的概念可以追溯到人类的起源。如果部落中的人们需要食物,他们会聚集在火堆周围,召唤猎人,告诉他下一次狩猎时食物的必要性,然后猎人会被迫(出于责任和良心)第二天出去打猎,尽最大努力为部落带回食物。在这里,我们可以想象人类以社会进步名义而不顾个人欲望的行为的第一个迹象。当然,猎人不是唯一一个有能力找到和运回食物的人,但是他已经接受了这个角色,并且在被要求这样做时尽自己最大的能力去做,仅仅因为事实就是这样。

Conversely, the word “Propaganda” is a relatively new term and is most often associated with ideological struggles in the twentieth century. The American Heritage Dictionary delivers a relatively simplistic definition of propaganda as the systematic propagation…of information reflecting the views and interests of those advocating such a doctrine or cause. In other words, assertions given by those who support them.

相反,「宣传」这个词是一个相对较新的词,往往与二十世纪的意识形态斗争联系在一起。美国传统词典给出了一个相对简单的定义:宣传是信息的系统传播,反映了那些主张这种教条或观点的人的观点和利益。换句话说,那些支持他们的人给出的论断。

政治攻击广告 —— 马可·卢比奥、希拉里·克林顿、唐纳德·特朗普、巴拉克·奥巴马、米特·罗姆尼、约翰·卡西奇

政治攻击广告 —— 马可·卢比奥、希拉里·克林顿、唐纳德·特朗普、巴拉克·奥巴马、米特·罗姆尼、约翰·卡西奇

The first documented use of the word ‘propaganda’ was in 1622, when Pope Gregory XV attempted to increase church membership by strengthening belief (Pratkanis & Aronson, 1992). Whether for the betterment of the congregation or the institution, Pope Gregory XV sought to directly influence theological “belief”. The relevance of this event lies in the fact that the focus of modern propaganda, as we speak of it, is a manipulation of belief. Beliefs, those things known or believed to be true, were realized even in the seventeenth century to be important foundations for both attitudes and behavior and therefore the essential target of modification.

第一次使用「宣传」这个词是在 1622 年,当时教皇格雷戈里十五世试图通过加强信仰来增加教会成员(Pratkanis & Aronson, 1992)。无论是为了改进教会会众还是制度,教皇格雷戈里十五都试图直接影响神学的「信仰」。这一事件的相关性在于,正如我们所说的,现代社会中宣传的焦点是对信仰的操纵。信仰,即那些已知或被认为是真实的东西,早在十七世纪就被认为是态度和行为的重要基础,因此也是改变的基本目标。

In Europe propaganda was quite impartial during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries describing various political beliefs, religious evangelism and commercial advertising. Across the Atlantic, however, propaganda sparked the creation of a nation with Thomas Jefferson’s writing of the Declaration of Independence. The popularity of literary propaganda had spanned the globe and the medium was made famous in the writings of Luther, Swift, Voltaire, Marx, and many others. For the most part, propaganda’s ultimate goal throughout this time was the increased awareness of what their author’s genuinely believed to be truth. It was not until the First World War that the “truth” focus was reconsidered. Around the world, advances in warfare technology, and the sheer scale of the battles being fought, made traditional methods of recruiting soldiers no longer sufficient. Accordingly, newspapers, posters and the cinema, the various media of mass communication, were used on a daily basis to address the public with calls to action and inspirational anecdotes – with no mention of lost battles, economic costs, or death tolls. As a result, propaganda became associated with censorship and misinformation as it became less of a mode of communication between a country and its people, but a weapon for psychological warfare against the enemy.

在欧洲,18 世纪和 19 世纪的宣传是相当公正的,它描述各种政治信仰、宗教福音传道和商业广告。然而,在大西洋的另一边,伴随着托马斯·杰斐逊所写的《独立宣言》。文学性宣传的流行已经遍及全球,这种媒介因为路德、斯威夫特、伏尔泰、马克思和许多其他人的著作而闻名。在大多数情况下,这一时期宣传的最终目标是提高对作者真正认为的真理的认识。直到第一次世界大战,所谓的关注「真相」才被重新考虑。在全世界范围内,战争技术的进步和战斗规模的扩大,使得传统的招募士兵的方法不再足够。因此,报纸、海报和电影作为大众传播的各种媒介,每天都被用来呼吁公众采取行动,讲述鼓舞人心的事迹 —— 但失败的战役、经济损失和死亡人数闭口不谈。因此,宣传逐渐与审查制度和错误信息联系在一起,因为它不再是一个国家与其人民之间的沟通方式,而是一种对敌人进行心理战的武器。

美国、爱尔兰和加拿大号召行动宣传海报

美国、爱尔兰和加拿大号召行动宣传海报

The tremendous importance of propaganda was soon realized and the United States organized the Committee on Public Information, an official propaganda agency, whose goal was to raise public support of the war. With the rise of mass media, it soon became apparent to the elite that film would prove to be one of the most important methods of persuasion. The Germans regarded it as the very first and most vital weapon in political management and military achievement (Grierson, CP). By World War II, propaganda was adopted by most countries - except those democratic countries who avoided the negative connotation the term, and instead cleverly distributed information through the guise of “information services” or “public education.” Even in the US today, the methods of providing and the learning of knowledge are deemed “education” if we believe and agree with those propagating the information, and considered “propaganda” if we do not. Not coincidently, central to both education and propaganda are the roles of the fact, the statistic, and that which the target believes to be true.

宣传的巨大重要性很快被认识到,美国组织成立了公共信息委员会,这是一个官方宣传机构,其目标是提高公众对战争的支持。随着大众传媒的兴起,精英阶层很快意识到电影将被是最重要的说服方法之一。德国人认为它是政治管理和军事成就中最重要的第一武器 (Grierson, CP)。到了第二次世界大战,宣传被大多数国家采用 —— 那些避免使用其负面含义的民主国家除外,但是他们巧妙地通过「信息服务」或「公共教育」的伪装来传播信息。即使在今天的美国,如果我们相信并同意那些传播信息的人,那么提供知识和学习知识的方法就被视为「教育」,如果我们不这样认为,就被视为「宣传」。并非巧合的是,教育和宣传的核心是事实、统计数据以及目标人群认为是真实的东西。

Propaganda’s modern connotation is that of mass persuasion attempts to domineer established beliefs. However, great thinkers and theorists have been studying persuasion as an art for most of human history. In fact the persuasion of a viewing party has been an important discussion in human history ever since Aristotle outlined his principles of persuasion in Rhetoric. With the birth of modern technology and the development of film, propaganda became a significant and perhaps the most highly effective form of persuasion through the utilization of one-way media. As early as 1920, a scientist named Lippman proposed that the media would control public opinion by focusing attention on selected issues while ignoring others. And it is no secret that the vast majority of people obediently think as they are told. It’s just human nature - who has the time or the energy to sort out all the issues one’s self? The media does this for us. Censorship and one way media protect the few from extraneous or divertive impulses that might lead him to examine the new reality in a way that doesn’t harmonize with the director’s intent. It offers us safe, often comforting opinions that appear to be the consensus of the nation. It appeals to the masses “through the manipulation of symbols and of our most basic human emotions” to achieve its goal - that of the viewer’s compliance.

宣传的现代内涵是大规模的说服,并以此试图控制已经建立的信仰。然而,伟大的思想家和理论家在人类历史的大部分时间里都把说服作为一门艺术来研究。事实上,自从亚里士多德在《修辞学》一书中概述了他的说服理论以来,对人群的说服一直是人类历史上的一个重要讨论。随着现代技术的诞生和电影的发展,通过利用单向媒体,宣传成为一种重要的、也许是最有效的说服形式。早在 1920 年,一位名叫利普曼的科学家就提出,媒体可以通过把注意力集中在选定的问题上而忽略其他问题,从而控制公共舆论,而且绝大多数人会顺从地按照别人告诉他们的那样去思考,这也不是什么秘密,这只是人类的天性 —— 谁会有时间和精力自己整理所有的问题?媒体为我们做了这些工作。审查制度和单向媒体保护少数人免受外来或转移性的冲击,这些冲击可能导致他以与官方意图不一致的方式审视新的现实,并且提供了安全的,往往是令人感到愉悦的意见,似乎是整个国家的共识。它「通过操纵符号和我们最基本的人类情感」来吸引大众,以实现其目标 —— 受众的顺从。

Compliance is an easy and immediate solution to a social problem. Compliance does not require the target to agree with the campaign, just simply perform the behavior. Such an accomplishment was not easily attained, and it took some of the greatest, and most vicious, minds of our time to do so effectively.

顺从是解决社会问题的一个简单而直接的办法。顺从并不需要人们同意运动,只需执行行动即可。这样的成就不容易取得,它需要我们这个时代一些最伟大、最邪恶的头脑才能有效做到。

Propaganda adheres wholeheartedly to the moral that the supreme good is the confusion and defeat of the enemy. The propagandist must have a full understanding the words and images that portray his message and a method to deliver the combination in a way to implant the message with out divulging that it is doing so. John Grierson argues that free men are relatively slow on the uptake in the first days of crisis… (and) your individual trained in a liberal regime demands automatically to be persuaded to his sacrifice… he demands as of right—of human right—that he come in only of his own free will. Great propagandists are successful because they have a great understanding of how to reach the heart of the masses. To borrow an example from Dr. Kelton Rhoads, they went beyond simplistic thinking like, “What can we say to make people decide to buy a car?” but rather, “What makes people decide to say yes to all sorts of requests - to buy a car, to contribute to a cause, to take a new job?”

宣传坚信这样一个道德观念:最高追求就是迷惑和击败敌人。宣传者必须充分理解描绘他的信息的文字和图像,以及掌握一种既能灌输信息同时又不会暴露这种做法的方法。约翰·格里尔森认为,在危机爆发的头几天,自由人的反应相对较慢…… 而且,在自由政体中受过训练的个人会自动要求被说服,接受自己的牺牲…… 他要求自己完全出于自愿,这是一项人权方面的权利。伟大的宣传者之所以成功,是因为他们深知如何触及民众的内心。借用凯尔顿·罗兹博士的一个例子,宣传者超越了简单化的想法,比如,他们不会想「我们能说什么让人们决定购买汽车?」,而会想「是什么让人们决定接受各种各样的请求 —— 购买汽车、为某项事业做贡献或者接受一份新工作?」

One person who had full knowledge and took full advantage of man’s inherent vulnerability was Adolf Hitler. Considered the greatest master of scientific propaganda in our time by John Grierson, Hitler said outright, ‘…the infantry in trench warfare will in future be taken by propaganda… mental confusion, contradiction of feeling, indecisiveness, panic; these are our weapons.’ Sun Tzu said, to subdue the enemy without fighting is the highest skill. Hitler had such a skill, and by utilizing his “weapons” Hitler was able to predict and cause the fall of France in 1934, as well as strike fear in the eyes of outside nations while rousing the hearts and courage of a rising army within.

阿道夫·希特勒是一个充分了解并充分利用人类固有弱点的人,被约翰·格里尔森称作我们这个时代最伟大的科学宣传大师。希特勒直截了当地说道,「…… 堑壕战中的步兵,将来会被宣传所占领…… 精神混乱、感情矛盾、优柔寡断、恐慌,这些就是我们的武器。孙子说,不战而屈人之兵是最高的技能,希特勒拥有这样的技能,通过使用他的「武器」,希特勒能够预测并导致 1934 年法国的沦陷,同时在其他国家的眼中制造恐惧,同时唤醒内部崛起的军队的内心和勇气。

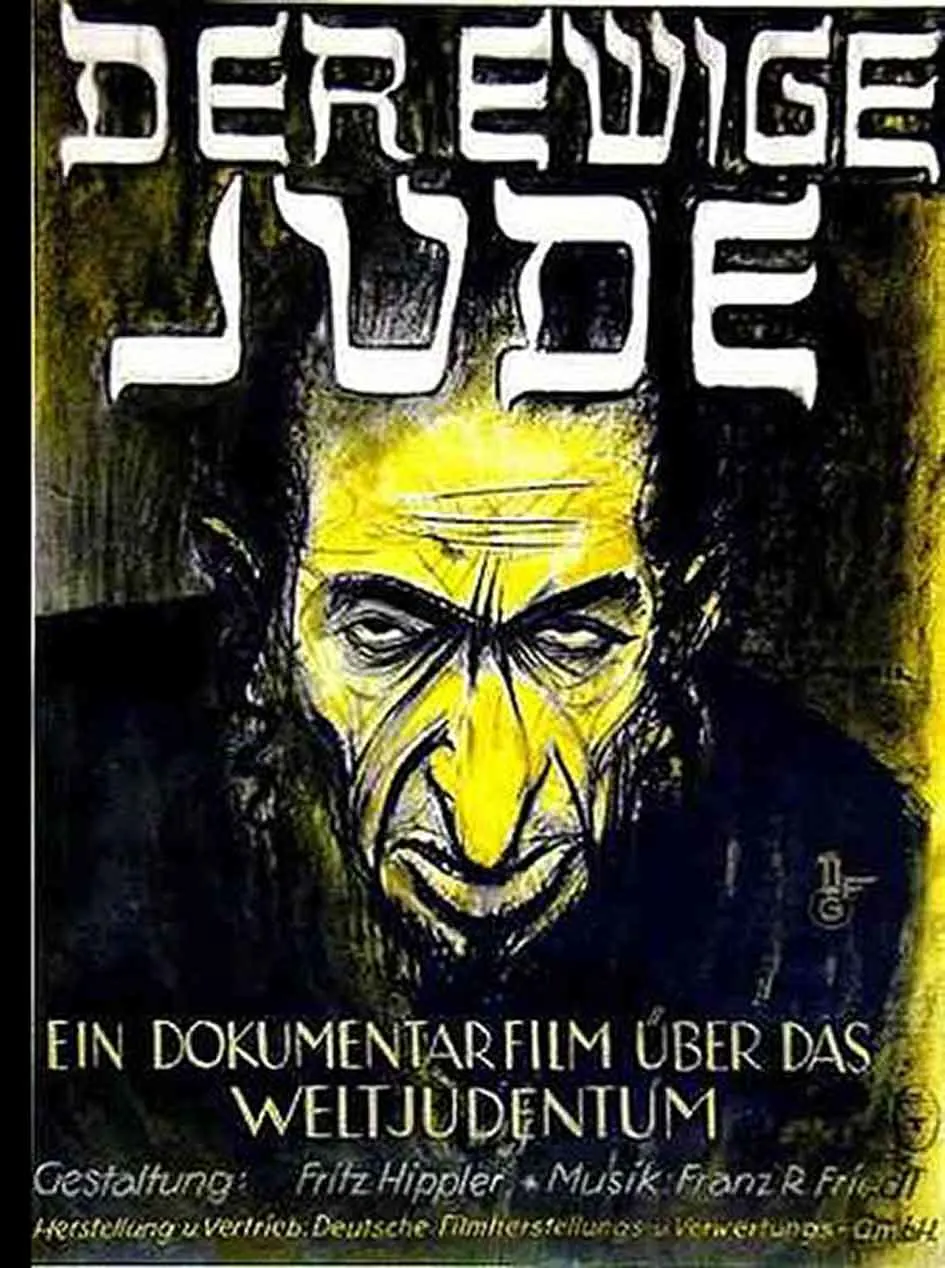

1940 年上映的《永恒的犹太人》是一部反犹太主义的纳粹宣传片,被宣传为纪录片。由约瑟夫·戈培尔制片,弗里茨·希普勒导演。

1940 年上映的《永恒的犹太人》是一部反犹太主义的纳粹宣传片,被宣传为纪录片。由约瑟夫·戈培尔制片,弗里茨·希普勒导演。

Propaganda relies heavily on different tactics of persuasion to manufacture a specific belief in the mind of the viewer. Depending on who you ask there ranges anywhere from two to over ninety tactics that exist on many levels and degrees of intensity. To be effective, propaganda has to make a complex idea simple as its success is based on the manipulation and repetition of these ideas. In looking directly at Hitler’s use of propaganda film we will put our focus towards its reliance on confusion of fantasy and reality through the style of realism and extratextual conditions.

宣传在很大程度上依赖于不同的说服策略,在受众的头脑中制造出一种特定的信仰。根据你询问对象的不同,有两种到超过九十种不同强度的战术可供选择。为了有效,宣传必须使一个复杂概念简单化,因为它的成功是基于对这些想法的操纵和重复。观看希特勒对电影宣传片的运用,我们可以通过现实主义的风格和其他条件,发现宣传的重点在于对幻想与现实的混淆。

The most notorious of the Nazi “fantasy/reality” films is called “The Eternal Jew.” Under the insistence of Joseph Goebbles, this film was assigned to and produced by Fritz Hippler as an anti-Semitic “documentary”. Characteristic of Hippler, this film, often called the “all-time hate film”, relied heavily on narration in which anti-Semitic rants coupled with a selective showing of images including pornography, swarms of rodents, and slaughterhouse scenes that alleged to display Jewish rituals. His footage showed masses of the hundreds of thousands of Jews that were herded into the ghetto, starving, unshaven, bartering their last possessions for a scrap of food and described the horrific scene as Jews “in their natural state.” He showed rats scurrying in droves from the sewers and leaping at the camera while the narrator comments on the spreading of the Jews “like a disease” throughout Europe: “Wherever rats turn up, they spread annihilation throughout the land… Just like the Jews among mankind, rats represent the very essence of malicious and subterranean destruction.” Hippler dutifully provides before and after photos of Jews attempting to hide their true selves behind a façade of civilization allowing German audiences to recognize them for who they truly are and not be fooled by there cheating, filthy, parasitic species. The audience is then provided a supposed history on the Jew and his deceptive ways. This is done so by showing “documented” scenes from the fiction film The House of Rothschild. We see a rich Rothschild, played by George Arliss, hiding food and changing into ratty old clothing to deceive and cheat the tax collector, and are expected to accept it as fact rather than a Hollywood production. The film goes so far as to single out Albert Einstein (at this time already quite famous) by showing his picture with the commentary: “The relativity-Jew Einstein, who concealed his hatred of Germany behind an obscure pseudo-science.” Though seeming absurd today, the film acted then to incite an anxiety and confusion in the German people at the threat of a thriving disease-ridden people, and seemingly no solution for the problem. The climax of the film is a powerfully disturbing warning and declaration of hate by Hitler himself assuring the people that there is no problem. Taken from a speech to the Reichstag in 1939 it translates as:

纳粹最臭名昭著的「幻想/现实」电影被称为《永恒的犹太人》。在约瑟夫·戈布尔斯的坚持下,这部电影被分配给弗里茨·希普勒制作,作为一部反犹太主义的「纪录片」。这部通常被称为「史上最仇恨」的电影,有着希普勒的特点,它主要依赖于反犹太主义的夸夸其谈,加上有选择性地展示色情、成群的啮齿动物以及据称展示犹太仪式的屠宰场场景等图像。希普勒的录像显示,成千上万的犹太人被赶进犹太居住区,忍饥挨饿,胡子拉碴,用他们最后的财产换取一点食物,他还把这个可怕的场景称作犹太人「处于自然状态」下。展示了成群结队的老鼠从下水道里窜出来,对着镜头跳跃,而解说者则评论犹太人「像疾病一样」在整个欧洲蔓延:「无论老鼠出现在哪里,它们都会在整个土地上散布灭绝…… 就像人类中的犹太人一样,老鼠带着恶意和地下破坏的本质。」希普勒尽职尽责地提供了犹太人试图在文明外表下隐藏真实自我的前后照片,让德国民众认识到他们的真实身份,不要被这些欺骗、肮脏、寄生物种所愚弄,然后向民众提供一个关于犹太人极其欺骗方式的假想历史。这可以通过放映科幻电影《罗斯柴尔德家族》中的「记录」场景来展现,我们可以在其中看到一位富有的罗斯柴尔德(由乔治·阿里斯扮演)藏匿食物,换上破旧的衣服,来欺骗和糊弄税务人员,并期望观众接受电影中的场景就是事实,而不是一个好莱坞制作商。这部电影甚至把阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦(当时已经相当出名)单独挑出来,展示了他的照片并评论:「犹太人爱因斯坦的相对论,用一种晦涩的伪科学掩盖了他对德国的仇恨。」尽管今天看起来荒谬无比,但是这部电影在德国人民中引发了焦虑和困惑,让人们认为德国正面临着疾病肆虐的犹太人的威胁,而且似乎没有解决办法。影片的高潮部分是希特勒本人发出的一个强有力的令人不安的警告和仇恨的声明,他向人们保证没有问题。摘自 1939 年希特勒在德国国会的一次演讲,译文如下:

If the international finance-Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations into a world war yet again, then the outcome will not be the victory of Jewry, but rather the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!

如果欧洲内外的国际金融领域的犹太人再次成功地将各国卷入世界大战,那么结果将不是犹太人的胜利,而是犹太人在欧洲的灭绝!

Closure comes in the foreboding words of Hitler as he adamantly proclaims that all of these troubles will soon be taken care of.

希特勒用不祥的话语结束了这一切,他坚定地宣称,所有这些麻烦都将很快得到解决。

Although this passing off of fiction footage as documented truth is today simply embarrassing and completely counter-effective, it was not an entirely new concept at the time. In reality, the method of sampling footage from other films to enhance your own was becoming quite common. In America, for instance, it was feared by officials that anti-war and anti-foreign entanglement feelings prevailed between the wars, and in general the ordinary American didn’t give “a tinker’s dam” about Hitler (Rowen, 2002). The Army had actually been producing hundreds of training films but Chief of Staff George C. Marshall was looking for something different. He mapped out objectives and hired Hollywood director Frank Capra to carry out his proposed Why We Fight film series, essentially to justify fighting in such a long and costly war. But along with the arduous task of completing Marshall’s 6 objective plan, Capra undertook perhaps the one most basic and fundamental objective that a film used in troop information sessions had: holding the audience’s attention. As such, it was necessary to have footage that was not only exciting but displayed a positive outlook on the war for “our boys,” no matter the source. This is a major reason why “The Nazis Strike” and the Why We Fight series in general are probably best described as compilation films rather than documentary and therefore very much a job of effective editing. Set on the objective of boosting moral, Capra hired Hollywood actor Walter Huston as a narrator, commissioned Disney to produce maps and animation through an agreement with the government, and cut between footage from US Federal programs and, a propaganda masterpiece, Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will to keep a fast paced and interesting series of films.

虽然这种将虚构的镜头作为真实记录的做法在今天看来是令人尴尬和完全无效的,但这在当时并不是一个全新的概念。事实上,从其他电影中截取镜头以增强自身说服力的方法已经变得相当普遍。例如,在美国,官员们担心反战和排外情绪在战争时期占据上风,而普通美国人对希特勒的态度不屑一顾 (Rowen, 2002)。美国陆军实际上已经制作了数百部训练影片,但参谋长乔治·C·马歇尔在寻找一些不同的东西。他制定了目标,并聘请好莱坞导演弗兰克·卡普拉拍摄他提出的《我们为何而战》系列电影,本质上是为了证明参与这样一场旷日持久、耗资巨大的战争是正当合理的。但是,在完成马歇尔的 6 个目标计划的艰巨任务的同时,卡普拉也承担了一个或许是最基本也最根本的目标,这个目标是一部用于军队信息会议的电影所具备的:吸引观众的注意力。因此,有必要拍摄一些不仅能振奋人心,而且可以展示「我们的孩子们」对战争积极看法的镜头,不管来源如何。这就是为什么《纳粹的攻击》和《我们为何而战》系列通常被描述为汇编影片而不是纪录片的一个主要原因,因此,这是一项非常有效的编辑工作。为了达到增强士气的目标,卡普拉雇佣了好莱坞演员沃尔特·休斯顿作为解说员,通过与政府的协议委托迪斯尼制作地图和动画,剪辑美国联邦节目的镜头和宣传杰作、莱尼·瑞芬斯塔尔的《意志的胜利》 ,以保持一个快节奏和有趣的系列电影。

希特勒在《意志的胜利》中的标志性形象。雷尼·莱芬斯泰尔运用娴熟的电影技巧,将希特勒塑造成一个强大的人民救世主。

希特勒在《意志的胜利》中的标志性形象。雷尼·莱芬斯泰尔运用娴熟的电影技巧,将希特勒塑造成一个强大的人民救世主。

Upon its release in 1935, Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, a documentary of the sixth Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg, displayed beyond doubt the power of propaganda film. Hitler’s descent from the sky in a shiny silver airplane presents him as a deity on the helm of technological achievement. Always looking down upon the people he so cares for, his demeanor is always pleasant. In fact the only time he gets riled up is for a speech, and then we get see just how energetic and passionate he can be when it comes to achieving the best for his country and its people. Through an extraordinary choreography of images and sounds, from marching men, swastikas, cheering women and children, and folksongs, the film inspired some, terrified others, and ultimately rallied many to the Hitler cause. No film was more widely used by opposing forces to vividly display the wicked nature of its enemy than Triumph of the Will. Striking a blow against the opposition by provoking fear while at the same time calling to arms the loyalty of thousands upon thousands, this tremendous outpour of emotion and action as a result of masterful imagery and film editing is the epitome of what propaganda stands for.

1935 年,莱尼·瑞芬斯泰尔的《意志的胜利》在纽伦堡纳粹党第六次代表大会上上映,毫无疑问,它展示了宣传电影的力量。希特勒驾驶着一架闪亮的银色飞机从天而降,成为掌管技术成就的神明。总是看不起他所关心的人,他的举止总是令人愉快的。事实上,他唯一一次被激怒是因为一次演讲,然后我们就会看到,当谈到为他的国家和人民争取最好的结果时,他是多么精力充沛和充满激情。通过出色的图像和声音编排,从游行的群众、纳粹十字记号、欢呼的妇女和儿童、民间歌谣,这部电影鼓舞了一些人,吓坏了其他人,并最终团结许多人支持希特勒的事业。没有哪部电影比《意志的胜利》更广泛地被敌对势力用来生动地展示敌人的邪恶本质。通过激起恐惧,同时号召军队中成千上万的忠诚力量,对反对派进行打击,这种精湛的影像和电影剪辑所产生的巨大情感和行动流露,是宣传所代表的缩影。

German audiences reacted to The Eternal Jew with cheers at the suggestion of the annihilation of the Jewish race in the film. Reminiscent of Cicero and his renowned ability in ancient Rome to demonstrate murdering villains as laudable patriots and have them subsequently acquitted, Hipple presents Hitler, (apparently) convincingly to Germans, as a hero rather than a eradicator for his plans to extinguish an entire race of people. Reifenstahl edits in the sounds of roaring crowds at the conclusion of the descent of Hitler in his flying machine from the heavens above. In Triumph of the Will, the Fuhrer was a gentle simple soul, serving his people, humble in his triumphs. Capra, in turn, used the tools of Hollywood to glamorize and rally up our troops in support of a war that was killing thousands and costing millions. What we come to realize is that very little importance is given to whether or not propaganda is true, but rather it is whether or not it gets someone to act. In these cases they did exactly that.

德国民众对《永恒的犹太人》中犹太种族灭绝的暗示反应强烈。希普把希特勒(显然)令人信服地呈现给德国人,把他塑造成一个英雄,而不是一个消灭整个民族计划的根除者,这让人想到西塞罗,以及他在古罗马那种声名显赫的能力 —— 将杀人的恶棍说成值得称赞的爱国者,并随后将他们无罪释放。当希特勒驾驶着他的飞行器从天而降的时候,瑞芬斯泰尔在喧嚣的人群中编辑剧本。在《意志的胜利》中,元首希特勒是一个温文尔雅的朴素形象,为人民服务,在胜利面前十分谦逊。另一边,卡普拉利用好莱坞的工具来美化和召集我们的军队,支持这场杀死成千上万人、耗资数百万的战争。我们逐渐意识到,宣传是否真实并不重要,重要的是它是否能让人采取行动。在这些案例中,他们就是这么做的。

Conversely, with the rising popularity of injecting the masses with beliefs, there came another movement in direct opposition: film which sought to control the sub-consciousness of a people. Leading the way was surrealist Luis Bunuel with his stunning satire Land Without Bread. Bunuel took a village of average people from the mountains of Spain and created a sad, decrepit world full of misery and death simply to mess with your head. The statement he was making was in fact quite bold and executed so well that it made you seriously question your susceptibility to deception. His portrayal of tragic scenes of an unlucky goat, and, you are told, starving children who have to stay at school to eat their bread for fear of it being stolen by their greedy parents, accompanied by a soundtrack of heroic and upbeat music works effectively to pry apart your acceptance of what is real and question what it is you are watching.

相反,随着向大众灌输信仰的日益流行,出现了另一场直接对立的运动:试图控制一个民族潜意识的电影。最著名的代表作就是超现实主义作家路易斯·布努埃尔令人惊叹的讽刺作品《没有面包的土地》。在西班牙山区的一个普通村庄,布努埃尔为读者描绘了一个悲伤、破旧、充满痛苦和死亡的世界,这足以扰乱你的头脑。他所说的话实际上相当大胆,而且执行得很好,使你认真地怀疑自己是否容易受到欺骗。他描述了一只不幸的山羊的悲剧场景,同时你被告知,饥饿的孩子们不得不呆在学校吃面包,因为他们害怕面包被贪婪的父母偷走,伴随着英雄主义和乐观向上的音乐,有效地撬开了你对真实的接受,并质疑你正在看的是什么。

In a complete opposite method, John Huston’s Battle of San Pietro seeks to dispel our skepticism in the legitimacy of film by divulging as much information in the most descriptive details possible as to leave no question of its sincerity. This abundance of information acts to put you in the place of a real soldier as you follow, side by side with the infantry, watching the action, even experiencing the death of fellow soldiers as we see the life extinguished of two people, both from in front and behind the camera. Its chilling realism sought to let you have the whole experience on your own rather than edit out the bad parts.

用一种完全相反的方法,约翰·休斯顿的《圣皮耶特罗之战》试图通过在尽可能多的描述性细节中透露尽可能多的信息,来消除我们对电影合理性的怀疑,从而不会怀疑它的真实性。这些丰富的信息使你置身于一个真正的士兵所在的位置,与步兵肩并肩,观察行动,当我们看到两个人的生命从摄像机前面和后面消失时,甚至能感受到同伴的死亡。它那令人毛骨悚然的现实主义试图让你拥有自己的全部体验,而不是删除那些不好的部分。

Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog served two purposes. That of a vigorous indictment, and that of a lesson for those to come. He frequently shifts back and forth from warm colored, serene images of the former extermination camps to horrific black and white images of the carnage they produced. In a time when documentarists were in no way being subtle about the films they made, Resnais used his film to take a calm and composed look back at the horrific incidences that took place and at the death camps and establish a need, not for acceptance, but for remembrance. He used film in a shockingly beautiful and gruesome way to express the importance of not forgetting those that were lost.

阿兰·雷乃的《夜与雾》有两个目的。一是一种有力的控诉,同时也是对将来人的一种教训。电影经常从种族灭绝营建立前温暖、宁静的画面转换到他们制造的大屠杀的可怕的黑白影像。在纪录片制作人对他们拍摄的电影毫不含糊的时代,雷乃用他的电影冷静而沉着地回顾了发生在死亡集中营中的可怕事件,并且建立了一种责任,不是接受,而是纪念。他用一种令人震惊的美丽和可怕的方式,通过胶片来表达不要忘记那些已经逝去的人的重要性。

There is an insidious psychological process called the “Self-serving Bias.” This bias leads us to believe that we are immune to the influences that affect the rest of humanity. And it is that belief that these three film makers were directly aiming at exploiting. They rely more on an empathetic identification than anything else. By eliciting a strong emotional response from the viewer, the viewer is persuaded to believe his feelings take precedence over an authoritative or legislated principle or rule. For example, modern Christianity tends to see the Ten Commandments as mood oriented suggestions rather than moral absolutes. If our feelings are strong enough, then God will grant dispensation. “It just seemed to be so right for me”…..denies authority to “thou shalt not commit adultery” for example.

有一种潜在的心理过程叫做「自利性偏差」,这种偏见使我们相信,影响其他人类的影响对自己是免疫的。这正是这三位电影制造者直接瞄准利用的人。他们更多地依赖于同理心的认同而不是其他任何东西。通过引起观众强烈的情感反应,观众就会相信他的感受优先于权威的、通过立法制定的的原则或规则。例如,现代基督教倾向于将十诫视为情绪导向的建议而非绝对的道德。如果我们的情感足够强烈,那么上帝就会给予我们豁免。「这对我来说似乎太合适了」…… 例如,否认「不可通奸」的权威。

Dr. Kelton Rhoades delivers the example to television watchers old enough to remember the Kung Fu television program. “Whose side were you on when the prejudiced, muscle-bound drunk lunged at peace-loving David Carradine with a broken beer bottle? Did you enjoy watching Carradine turn the enraged belligerent’s charge into a devastating floor-slam? The point is that these films invoke a sense of emotion that suddenly makes us realize a truth only when we look within ourselves and acknowledge that the so-called “greater good” is not always the greatest good; and often it’s not good at all.

凯尔顿·罗德斯博士把这个例子告诉给那些足以记住《功夫》电视节目的电视观众,「当一个充满偏见、肌肉发达的醉汉拿着一个破啤酒瓶冲向热爱和平的大卫·卡拉丁时,你站哪一边?你喜欢看卡拉丁把这个激怒的交战者的冲动变成一个毁灭性的地板重击吗?问题在于,这些电影唤起了一种情感:只有当我们审视自己的内心,承认所谓的「更大的好」并不总是最大的好处,而且往往一点都不好时,这种情感才会突然让我们意识到一个真理。

The word “propaganda” is often invoked when it is obvious that objectivity in a film has ceased. The irony is that the term is invoked precisely when the film has failed as propaganda. When the choices please us, we do not mention it. In a sense, all film makers are propagandists as they try to create a mood for the viewer and invoke feelings to draw you into the story. Yet in all fiction, the viewer must maintain a willingness of disbelief. It is not a healthy mind that can watch the Terminator films and not realize that what they are seeing is fiction, no matter how realistic it looks and sounds. “Documentary” and “propaganda” on the other hand, and this is why they can be such manipulative tools, use supposed images of reality to create a story and therefore is seen by the viewer as not requiring that willingness of disbelief. You don’t have to constantly remind yourself that it isn’t real, because it is in fact, in one way or another, “real”, and that is enough to make you believe. As long as you think yourself insusceptible, there will be someone just above you pulling on a string; there will be someone there to pull a coin from behind your ear when you are not doing what you are supposed to.

「宣传」这个词经常被用来形容一部电影明显已经失去客观性。具有讽刺意味的是,这个词恰恰在一部电影作为宣传失败的时候被使用。当选择使我们高兴时,我们不会提及它。在某种意义上说,所有的电影制作人都是宣传者,他们试图在观众中营造一种情绪,并唤起情感来吸引你进入故事。然而,在所有的虚构场景中,观众必须保持一种怀疑的意愿,不管看起来和听起来多么真实。如果你看了《终结者》电影却没有意识到,你所看到的是虚构的,那么你就没有一个健康的头脑。另一方面,「纪录片」和「宣传」利用假定的现实图像来创作故事,因此被观众视为不需要怀疑的意愿,这就是为什么它们可以成为操纵工具的原因。你不需要不断地提醒自己这不是真实的,因为事实上,无论如何,这是「真实的」,就足以让你相信。只要你认为自己不受影响,就会有人在你上方拉着绳子;当你没有做你应该做的事情时,就会有人在你耳朵后面拔一枚硬币。